Marcelle Cook-Daniels

His Life and Struggles

(by

Gigi Kaeser)

(by

Gigi Kaeser)

This article originally appeared in the

issue of The Washington Blade on

May 5,

2000

May 5,

2000

E-mail The Washington Blade

Copyright © 2000 The Washington Blade Inc

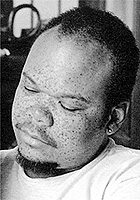

Marcelle Y. Cook-Daniels, 40, died April 21 as a result of

suicide, following a lifelong battle with clinical depression,

according to his partner of 17 years, Loree Cook-Daniels.

Cook-Daniels was well known as an educator and advocate in the

movements for transgender and Gay equality, having presented at

the 1999 Creating Change conference, the "Butch-FTM: Building

Coalitions Through Dialogue" event in 1998, and several True

Spirit conferences.

Marcelle Cook-Daniels was born March 1, 1960, in Washington,

D.C., and lived here until moving to Vallejo, Calif., in 1996.

Having earned a bachelorís degree in computer science from the

University of Maryland in 1990, Cook-Daniels worked as a

computer programmer/analyst for the IRS and the

Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission.

Cook-Danielsís most recent position was with the Norcal Mutual

Insurance Company in San Francisco. At the time of his death, he

was also completing coursework to earn his masterís degree in

computer science at Golden Gate University.

"The primary thing [Marcelle] leaves is his son, Kai," said

Loree Cook-Daniels, referring to their 6-year-old son. "And he

leaves the model of a man who was very, very devoted to his

family. Devoted to ensuring that his family got the respect and

rights that should be accorded to anyone and to any family."

Cook-Daniels also leaves a legacy of documents, in that

interviews with and photos of him appear in the book Love Makes

a Family, edited by Peggy Gillespie with photos by Gigi Kaeser;

in Looking Queer: Body Image and Identity in Lesbian, Bisexual,

Gay and Transgender Communities, by Dawn Atkins; and in In The

Family magazine. He also gave substantial material and volunteer

support to the Transgender Aging Network and The American Boyz,

a national organization for female-to-male gender-variant

people, according to Loree Cook-Daniels. "Iím not sure yet how

weíre going to carry on the work," she said of the void left by

Marcelleís death. "Certainly, weíre not going to abandon it."

In addition to his life partner Loree and his son Kai, Marcelle

Cook-Daniels is survived by many friends and colleagues.

A memorial service was held in Cook-Danielsís honor April 26 in

Vallejo. Loree Cook-Daniels said about 100 people attended. She

estimated about half those attending belonged to the

female-to-male transgender community and their "significant

others, friends, families and allies," or SOFFA. "We have gotten

a huge amount of support from the FTM and SOFFA community," she

said, adding that at the memorial, "lots of people talked about

the impact Marcelle had had on the FTM community."

Cook-Danielsís family has suggested that those wishing to honor

his memory may make a donation in his name to the Marcelle Y.

Cook-Daniels Memorial Fund, care of Children of Lesbians and

Gays Everywhere. Checks should be made out to COLAGE and be

accompanied by a note that the donation is intended for the

memorial fund. Donations should be sent to COLAGE at 3543 18th

St., No. 17, San Francisco, CA 94110.

TRANS-POSITIONED -- By Loree Cook-Daniels

First published in Circles Magazine, June 1998 (Circles Magazine

is published 6 times a year. Subscriptions: $24.95. 1705

Fourteenth Street, Suite 326, Boulder, CO 90302; 303/245-8815

(telephone); 303/245-8816 (fax); 888/633-0055 (subscriptions);

email:

info@circlesmagazine.com; website:

http://www.circlesmagazine.com.

She's the kind of butch any femme

would want: kind and thoughtful, mature and funny, politically

aware and playful, handsome and great in bed. You've been

soaring on cloud nine since the two of you got together.

There's just one little problem that threatens to bring the

whole wonderful lovership to a crashing halt.

She says that despite her female body,

she's actually a man. And she -- or should it be "he"? --

intends to live as one.

Dyed-in-the-wool, activist, out, proud lesbian feminist that I

am, I've always understood that the social myths that lesbians

just want to be men or actually want male lovers but can't catch

any are exactly that: myths. Confronted by my new lesbian love's

assertion that she was a female-to-male transsexual, I was

therefore more than a little confounded. No lesbian I'd ever

heard of had gone down this road before, and, I finally decided,

I was not going to be first. Tearfully, I gave my new love an

ultimatum: she could either have me or live as a man, but not

both.

For nine mostly-silent years I thought Marcelle and I were the

world's only lesbian feminist couple hiding one partner's

transsexual feelings. When I finally decided I could no longer

in good conscience block Marcelle's transition from female to

male, one of the tasks I most dreaded was having to tell

everyone who knew us as lesbians the truth: this particular

lesbian was, in fact, a man, and her -- his -- lesbian lover was

going to stay with him.

I expected rejection. I expected incredulity. I expected anger.

I expected curiosity. What I did not expect was what I found.

Out of the first 30 or so coupled lesbian friends we talked to,

three admitted that one of the partners felt she was

also a female-to-male transsexual (FTM). A fourth lesbian friend

said she had struggled with the question for many years before

deciding to keep her female body and role. During the whole nine

years Marcelle and I had grappled in isolation with that

invisible elephant in the living room, other lesbians we knew

and socialized with were cohabitating with the same beast!

Like the early feminists shocked into politicization as a result

of sharing their personal lives in consciousness-raising groups,

my discovery of the hidden undercurrent of transsexual feelings

in the lesbian community radicalized me. In part to atone for

the pain I'd caused Marcelle with my ultimatum, in part to

continue Marcelle's and my long-lived advocacy for our society's

"queers," and in part to ensure no other lesbian has to cope as

I did with a potentially transsexual partner in ignorance and

isolation, I've since made it a point to publicly discuss FTMs

in the lesbian community.

Luckily, other partners -- lesbian, bisexual, and straight, male

as well as female -- have been active, too. In the three short

years since Marcelle and I came out publicly about his

transsexuality, lots has happened: Five national conferences

devoted to female-to-male transsexuals which attracted some

partners have taken place; an e-mail list for partners of FTMs

has flourished; Minnie Bruce Pratt's book S/he about

her transgendered lover Leslie Feinberg was published; a 10-page

list of resources for "significant others" (SOs) of FTMs was

compiled; families that include an FTM and his lesbian lover

were included in nationally-distributed photographic displays

and magazine articles; and countless partners have met each

other at FTM-oriented groups...to name but a few of the

developments.

But the mushrooming of support and information networks for the

lovers of FTMs has not meant the road has been made smooth. The

struggles are still myriad, and many relationships do not

survive "transition" (the period during which a person changes

from living as a woman to living as a man). Yet having other

partners to talk to means having someone with whom one can ask

questions, compare notes, and vent. It's also allowed us to

start identifying patterns among partners' struggles. These

patterns seem to hold regardless of the partner's gender and

sexual orientation identity. Nevertheless, lesbian-identified

partners' identity issues differ some from heterosexual women's

identity issues, to take but one example. This article therefore

focuses particularly on the ways lesbian-identified SOs approach

the dilemmas.

You think you're a what?

Asked how she felt upon learning that her female lover believes

hirself(1) to be transgendered,

one woman answered: "Numb, unsure, afraid, happy for my partner,

scared, threatened, wanting to help my partner, needing help for

myself, depressed, restless, anxious, [and] happy that my

partner is finally able to express their true feelings."

Although most partners probably wouldn't be able to articulate

quite this extensive a range of feelings upon being told of

their lover's transsexuality, it does seem that contradictory

feelings are common: "My first thought was that I would have to

leave. That thought made me very sad after all we have built up

over the years. I hate to see that go down the drain. In fact, I

felt angry that I had to walk away. Why should I? No one has

ever loved me the way my partner does. How could I settle for

less? Why should I?" Another woman said, "I really don't think I

can or want to stay. Some of the time. At other times the

alternative seems much worse...I feel like I would be letting go

of a really important relationship for a 'little' thing like

gender, or a pronoun." A third acknowledged her doubts but

concluded, "I really want to see my lover more at peace with

himself on a daily basis. He just seems so tortured now."

With time, these initial gut-level, emotional reactions start

getting refined and begin to take shape as questions about

identity. Although these questions are all interrelated, they

can be roughly grouped into three categories: What does this (transsexuality)

make hir? What does it make me? And, what does

it make us?

So what does this mean about who

you are?

FTMs often say that they've always been

male; they're just making some physical and/or social

adjustments so that other people recognize that fact. That's not

how a lot of lesbian partners see the process. Although many

always saw and often much appreciated their lover's butchness,

they say what they prize is masculinity wrapped in a woman's

body; masculinity as displayed by a man often feels totally

different. One woman commented about a photograph in Loren

Cameron's seminal FTM book, Body Alchemy: Transsexual

Portraits (Cleis Press, 1996), showing Loren with his butch

lover: "The picture of Kayt and Loren arm-wrestling struck me

because the line where their hands met is the line of my desire.

Kayt is totally my type. Transgendered, male-identified in a

woman's body." Another responded to a discussion about the

sexiness of butches: "I know what you mean about the

attractiveness of that look in a woman that says, 'Don't fuck

with me,' but the same look in a guy feels threatening and

dangerous because society has ingrained that in us through years

of oppression and violence towards women. Thinking of my lover

as a 'man' reminds me of the mean men in my past." Some know why

this memory of past mean men is an extremely scary proposition:

"I am also a survivor of sexual abuse, mostly at the hands of

men, and I am afraid of how my partner's transitioning might

trigger me." Others can't articulate the source of their fear,

but know that it's there: "I just get nervous thinking about

being in bed with a man."

Lesbian-identified partners also worry that a transitioning

spouse may turn into Bubba, or expect her to become June

Cleaver. "I love him dearly, but if he starts wondering aloud if

I shouldn't iron his underpants, then we are gonna have

problems." On a more serious note, another woman said, "I've had

to deal with the idea that as my SO becomes a man, his power

increases. To me, men are closer than women to power,

power-grabbing behavior, yelling, and physical violence."

Although these women feel they know their partners' values and

goals, they worry that hormones will change him ("the cold voice

of fear is still whispering in the back of my head: 'He's only

saying that because he's not on testosterone yet! Wait til the

hormones kick in and he loses his mind!'"), or that experiencing

male privilege will make the FTM forget or abandon the feminist

principles by which he formerly lived.

So what does this make me?

Lesbian-identified partners also worry about how their own

identity might change. It's easy to define yourself as a lesbian

when everyone can see that your partner is a woman. When your

partner is a man, however, even a strongly-held sexual

orientation identity of "lesbian" may seem less defensible. One

woman said, "I'm very dyke identified. The possibility that he

might transition and 'become male' scares me because I feel like

my identity hangs in the balance." A self-described femme echoed

that feeling. "I'm really wary of giving up my identity for

someone else. That seems like such a stereotypical femme thing

to do -- 'it's o.k., honey, your identity is more important than

mine.'" On the other hand, insisting on a lesbian identity when

one has an FTM lover may feel like an undermining of his

right to self-define: "I can't in good conscience call myself a

lesbian and validate his gender identity when he isn't

identifying as a woman," one woman explained.

Some lesbians don't find the prospect of losing their lesbian

credentials all that daunting. "Where I'm from, it's been hard

to find a part of the lesbian community that fit my fat Latina

hi femme meat eating kinky sex self. Therefore, I don't have

much to lose." Another who has had bad experiences with

judgmental lesbian peers said, "I can't stomach those

womyny-womyny lesbian types who are so quick to judge. I think

bisexual people are the most welcoming component of the GLBT

community to transpeople: they 'get it' (on trans issues, on

inclusion, on my identity being flexible) more than the

monosexual folks do."

So what would that make us?

Nevertheless, potential loss of the lesbian community is a big

deal to many of the partners of individuals contemplating

transition. "Many in our respective lesbian communities may feel

that once-lesbian identified transfolk and those of us lesbeens

who love them are 'defectors,'" suggested one woman. Another

partner who was further along in the process confirmed this

happens. "The 'wimmin's' community suddenly assumes that since

we 'appear' hetero, we will just fit right in with all those

other hetero couples who have done absolutely no gender

analysis, etc., etc.." Yet, she says of herself and her partner,

"the truth is, we want to be in the dyke community.

That is where we both feel we belong." FTM partners also may

feel keenly the loss of the lesbian community. One woman

reported how "painful" it was for her to attend an FTM

conference and "hear guys post-transition talking about loss of

community, looking for a less 'straight' identity, missing

lesbian space even if that hadn't been quite right for them

before. It made me wonder where and how we will find community."

Some women admit they helped create the community norms they now

feel exclude them. "The problem is that I like to go to lezzie

clubs and lezzie events. We like to do these things

together. I would still go with friends to do the lezzie things

I want to do if it came to that, but I want to do things like go

dancing with my lover and not have to go to a straight club. The

other piece to this is that I am part of the problem! When I was

out dancing Friday night, there were a few couples I perceived

as 'straight' and also some boys there. Who knows what paths

their lives have taken, but I found myself being irritated by

their presence." Another accepted her exclusion on the same

basis: "Part of the difficulty in being with an FTM, at least

for me, is that it changes my identity from lesbian to a FTM's

SO. So if the event is for lesbians only, I don't go. I don't

think any less of the lesbian community because of that. I

worked for many years to create a space for lesbians to feel

safe and free to express themselves."

Lesbian-identified partners also worry a lot about what they'll

look like to outsiders if their partner becomes male. As one

woman put it: "Everyone will see me as straight. Damn." Femmes

who have long struggled with misperceptions of heterosexuality

seem to be especially fearful of what transition will bring. One

said, "I guess that being perceived as a heterosexual couple is

really going to be a blow for me because perceptually I

will fall into the 'heterosexual stereotype' in other people's

eyes, which is what I fought to get away from in the first

place. What I'm trying to say is I'm going to look like a 'wife'

and no one will know any better. I guess my insides would be

screaming, 'I am not what you see!'" Another could foresee a

less threatening but still irritating future: "So, okay, the

whole world may perceive me as a straight woman married to (or

at least living with) a straight man. This perception will carry

with it a trainload of gender stereotypes and expectations,

which will no doubt piss me off royally on some days and just

make me laugh up my sleeve on others."

Coping with transition

Resolving these identity and community worries and dilemmas

takes time, a luxury many partners are shocked to find they

don't have. Like coming out as gay, coming to terms with being

transsexual is often a long process that goes on internally for

months, years, or even decades before the person finally starts

telling others. Once a person reaches the stage of coming out

publicly, zhe's often ready or even anxious to begin acting on

the newly-embraced identity. That means that many

lesbian-identified partners of newly-proclaimed FTMs find their

partners racing toward transition with almost break-neck speed.

Even when things go a little more slowly, each step the

transsexual partner takes toward his true identity

represents a step away from the lesbian partner's

preferred identity. "While he's celebrating," one woman

summarized, "you may be crying and grieving over a loss."

It's also hard to pay attention to your own personal and

relationship issues when your partner is going through a life

event as all-consuming as changing from a female gender role to

a male gender role. "Transition is the central issue in our

relationship," one woman stated. "His struggle with gender is so

consuming to both of us that my issues in the world kind of get

lost. I spend an enormous amount of time focusing on him and his

choices. I really need to think more about what it is that I

want and what choices I need to make." Many partners struggle to

balance their desire to be a loving partner who understands and

meets the transitioning partner's heightened need for support

and solace and their own need to grieve and process the losses

and doubts they are themselves feeling. Finding and keeping this

balance is a frequent topic of discussion among FTM SOs.

Sex and Drugs

Vastly complicating the emotional and practical issues

lesbian-identified partners struggle with as their partners

embark on transitioning is what's called "The Big T" --

testosterone. Getting a prescription for testosterone is often

the first exciting, concrete step a new FTM takes. But starting

sex hormones means going through another adolescence as the body

and brain adjust to a sudden rush of powerful, body-altering

chemicals. Read that: mood changes. One harried partner said,

"It's like menopause and puberty all at once sometimes."

Also read that: increased sex drive. For some female partners,

this is a highly problematic development: "I think the T has

made him a sex crazied uncaring ass. He seems to think only of

himself. I feel like a whore at times," one angry lover said.

Others are delighted: "I love having sex with him. Sex in

transition is fun for me. I love when he gets in bed and says,

'look at my body.' He is happy about the changes. We have more

fun in bed because he can really be there in his body in bed

with me."

Some couples find transition triggers body image and

desirability doubts. The FTM may be concerned about how

attractive his lover will find his masculinized body, and the

female partner may worry, perhaps unconsciously, that since the

FTM has "rejected" his female body, he must not be very

attracted to her femaleness, either. Indeed, some FTMs

do have problems with their female body parts. A few women, for

instance, report that their partners do not allow vaginal

penetration: "It repulses him to be touched sexually in a way

that reminds him of his feminine body parts," said one. A few

FTMs also begin to define certain sex acts as "lesbian" and

refuse to participate in them any longer. Interestingly, exactly

which acts are so labeled differs from FTM to FTM. One partner

reported that several transsexual men she heard speak admitted

they don't like to use dildos because they remind them of "what

they don't have," while another woman said she'd found that

"some FTMs feel using their hands is too lesbian coded, as are

certain aspects of oral sex." Yet having a sense of humor and

being willing to find new terms for body parts helps, one woman

responded. "Cognitive dissonance week (his term for that time of

the month when he has to use 'masculine protection'(2))

is hard. We work around where he is at, and sometimes the right

word makes the difference. We work around those words which to

him seem so female-coded, especially in the heat of the moment."

Further complicating the sexual picture, female partners may

find that certain turn-ons no longer work. One woman went to an

FTM conference worried about her sexual attraction to men, and

was not reassured. "I was looking at the guys there and it

seemed that when guys transitioned, many lost/gave up the tough,

hard masculine edge that they had before. I'm not sure I'd find

that kind of masculinity appealing or 'acceptable' in a man, but

in butches it was something that always carried sexual power for

me. There were some guys there I could find sort of hot if

pushed, but it doesn't bode too well for me and my partner."

Being out in public

Transition is also problematic outside the house, particularly

during the period when an FTM may be viewed as female in one

situation, male in another. "There are times when we long for

the anonymity of the straight society, like, say, when we look

for a bathroom," one partner said. Couples also sometimes argue

over who controls the coming-out process, particularly if the

FTM wants to look like and be treated as a "normal guy" and his

lover highly values a more transgressive persona. "I continually

struggle internally with the issue of disclosure," said one

woman. Yet she believes "it's my partner's job/right/privilege

to choose whom he discloses to." Others find the dilemma more

problematic: "I really miss being a dyke. I find it is a lot

easier to casually come out as a dyke ('my girlfriend took me to

a movie...') than as an FTM SO ('my boyfriend took me to a movie

and by the way he used to be a woman...'). I can't figure out

how to be 'out' without jeopardizing his right to be out/not out

when he wants to, because he passes most of the time now."

When it ends

Many lesbian-identified partners -- even those who expected to

be supportive of their lovers' transition -- end up discovering

that the whole process is just too much for them to handle. One

of the few studies of FTMs' relationships found that

approximately half of the intimate relationships FTMs had

established with women pre-transition did not survive the

change.(3) Yet these break-ups

are not always because the lesbian-identified partner decides

she can't cope with having an FTM lover. Indeed, many partners

discover they actually have a preference for FTMs. One said, "If

my lover and I ever break up (which I hope won't happen), I can

see myself attracted to other FTMs. Now that I've been with my

lover, my immense desire and appreciation of transsexual men is

strong." Another woman whose partner "freaked out" and left her

for another woman just days after he had surgery to remove his

breasts said, "Ironically, after he left, things became more

clear for me. I realized that it was very unlikely that I would

have left him because of the transition. I've realized that I am

attracted to FTMs both pre- and post- hormones." So many

ex-partners of FTMs have decided they prefer FTMs, in fact, that

a new online support group has been formed to help such women

meet single FTMs.

Of course, one doesn't need to decide one's preference is FTMs

to maintain a relationship with one. What one does need

to do is find at least "good enough" answers to the three

identity dilemmas a transitioning partner presents one with: Who

does that make him? Who does that make me? And who does that

make us? The answers, not surprisingly, differ for each woman

and each couple. But again, there are some identifiable

patterns.

Discovering what kind of man he is

One of the most helpful breakthroughs I had in coming to terms

with Marcelle's desire to transition was the realization that

when I imagined Marcelle as a man, I no longer saw Marcelle.

What I saw instead was a generic man, and not a very nice one at

that. Whatever qualities I knew my long-term lover had no longer

existed in this stereotypical man, as though Marcelle's

personality and values were suddenly going to cede the premises

to the ghost of John Wayne.

Other women reach similar conclusions, particularly as

transition progresses and they discover testosterone does not

automatically create monsters. Instead of their lover adopting

all the negative aspects of masculinity, many are pleased to

discover he's becoming a calmer and happier version of the

person they already loved. "My lover will not BECOME anything

different than what and who she has been and he is. I know there

will be changes, but he will never be a "MAN," he will just be

[his name], with a body he loves and struts around in." Others

remember or discover that they have some power over what

behavior gets manifested around them: "As I am a radical

feminist, I have made it very clear what attitudes I will NOT

accept from my lover, nor from our son." Still others come to

realize that the problem isn't gender (or, more accurately, the

masculine gender), it's plain old power and control: "Anyone can

have power and control issues," pointed out one woman. "Keeping

men out of your life is no guarantee you can escape that."

Finding your own name

Some lesbian-identified partners retain their lesbian label

despite being partnered with a transsexual man. These women

frequently explain their stance by pointing out that if their

relationship broke up, they would only date women, or by

asserting that the source of a person's identity springs from

within, not from hir lover's body.

More often, however, previously lesbian-identified partners

adopt a middle ground that more comfortably accommodates a male

partner. Bisexual, queer, and femme are the most popular

self-identifications, reflecting a desire to be seen as anything

but straight. Indeed, making a commitment not to fall into a

straight stereotype is often a part of this identity resolution:

"It's up to me to make intelligent choices and make sure I don't

become Mrs. Cleaver!" one woman explained. Others aren't so

worried: "I think being queer is like losing your virginity.

Once you have left the straight world, you can't go back."

Sometimes FTM partners also help in this effort to find and stay

on queer land. "[My partner] adamantly maintains he is not a

straight man -- he's in a relationship with a femme, not with a

straight woman."

Making your own community

Of course, identity is closely aligned with community, and

finding a comfortable community post-transition is a challenge.

Because it's unlikely that a previously lesbian-identified

partner who is happy to blend into a heterosexual world will

blow her cover by getting involved in an FTM SO support group,

we have no idea how many partners find happiness in hetero land.

Some, though, relish being the fox in the hen house: "For me,

being queer in a straight world is a wonderful thing!"

Some women find an accepting community among bisexuals: "The

bisexual community is far more understanding and much more

open-minded than the lesbian community." Others are lucky enough

to live where an integrated "queer" community exists. Even then,

however, some of these women worry about the stability of the

welcome mat on which they stand: "I'm just glad I do so much

work in the queer community; hopefully no one would dare kick me

out entirely." Those blessed with online access can find a

vibrant FTM SO community there.

But finding a community that fully embraces both the

FTM and his female lover is difficult, and that loss of a place

where both partners are equally welcome can be a bitter pill to

swallow. "I still suffer from these occasional bouts of fear and

sadness about him not being a dyke anymore," one woman admitted.

Some couples become determined to make the community they want:

"As far as finding space for ourselves, we both do a lot of

public speaking on the matter, and I am convinced we just have

to make space by educating." Another answered, "How do you find

space together? You do what other groups (i.e., gay, lesbian,

black, hispanic, feminist, etc.) have done: you create it." And

progress is being made. The second-largest U.S. "FTM"

organization, American Boyz, actually bills itself as an "FTM

and soffa (significant others, friends, family and allies)

organization." It has been growing exponentially in part because

it provides conferences and support groups where partners are as

welcome (and as liable to be leaders) as their FTM lovers.

Moving beyond

Becoming an FTM requires negotiating body changes, role changes,

and changes in how others view you. The lesbian-identified

partners of FTMs endure the same changes. They must live with

the altering of a body they may have much loved. They must cope

with their lover's mood swings and the other physical and

emotional changes testosterone brings. They must adjust to the

new ways people react to their partners, and to the assumptions

that are made about them now that they appear straight.

They must learn how to defend their lesbian identity in a way

they never imagined, or abandon that identity and find (or

create) a new one.

For most FTMs, the exhausting and challenging process of

transition nevertheless represents the culmination of a

long-held dream or the righting of a very old wrong. Lesbian

partners, by contrast, are generally happy with their sense of

themselves in the world pre-transition; the adaptations they

must make are not ones that, left to their own devices, they

would have sought out. Yet these unexpected challenges can bring

rich rewards. One woman looked back on her process and wrote:

"I want to affirm both the hardships that can be oh so real

and the joys that can come from growing through the changes

together as my partner and I were ultimately able to do. A year

ago I could not have said this. My heart felt torn apart. I

could not believe it would be possible to get to the other side

of the upheaval in our lives. I could not fathom loving my lover

in a male form. Well it's been a long year. In retrospect, a

really rich year, full of surprises. I feel so lucky to have a

lover who was willing to hang in and honor my feelings even when

they were on the other side of the universe from his. I feel

incredibly impressed with myself both for honoring my

process and being able to honor his. So much of the time it did

not feel at all like we were doing it together, but now I see

that we did and I am in awe. I know that some partners need to

leave their relationship in order to take best care of

themselves. I am personally glad that I stayed in mine. We have

a great love and that's a treasure I want to keep."

Others say that living through a partner's transition from

female to male has deepened their cultural and political

understandings and commitments in ways they could have never

imagined. One said, "I have been a fairly hardcore feminist for

years, very 'anti-patriarchy' and all that good stuff, but the

more I learn about gay, lesbian, and transgender relationships,

the more I realize that negative aspects in our culture's

structure of relationships are about power and dominance rather

than gender per se. I don't think I can ever think about gender

in the same way again. Or love, for that matter." Another woman

summed it up beautifully: "I believe that our being out here

doing this soul-, mind- and heart-searching work serves to bring

another important dimension of diversity to the lesbigaytrans

world. After all, isn't questioning and redefining our world

what growth and life is all about?"

Loree Cook-Daniels, 43, Milwaukee, WI,

lives with her son Kai, 6, and near her partners michael

munson and Bear. Loree is the widow of Marcelle Cook-Daniels,

who bore their son Kai before his transition female-to-male (FTM).

Decades' long activists on Lesbian and Gay issues, the Cook-Danielses

concentrated on building bridges between the LGB and T(trans)

communities after Marcelle's transition, and on raising

awareness of SOFFA (significant others, friends, family, and

allies) issues within the trans communities. Loree is currently

rebuilding and redefining her personal and activist life. In

addition to bringing her awareness and experience of trans and

poly family issues, she brings her skills as a professional

writer and conflict resolution specialist to COLAGE.

![[IMAGE]](images/thinrain.gif)

Information about the resources for partners

of FTM transsexuals and transgendered persons mentioned in this

article:

o To get information about or subscribe to the

email support group for significant others of FTMs, e-mail:

.

o The e-mail address for single women

interested in FTMs is:

FTM n WWLT@aol.com.

o For a list of local support groups and other

resources specifically welcoming of or relevant to soffas of

FTMs, see the website at:

http://members.xoom.com/ftmsofaq/soffaresourcelist.html.

o For information about the American Boyz, see

its website at:

http://www.amboyz.org or write P.O. Box 1118, Elkton, MD

21922-1118.

1. Although FTMs are properly referred

to by masculine pronouns, pronouns present a problem for those

who are speaking of people who are still in the early stages of

exploring whether or not they are FTM and those who have chosen

to occupy a middle, blended gender ground. Although several

genderless pronoun systems exist, none has been adapted

universally. For this article, I've arbitrarily chosen to use "zhe"

and "hir" whenever a person seems not to identify with either

set of gendered pronouns and when I'm talking about both males

and females.

2. Regular

testosterone use does stop menses, but it may take several

months before this effect occurs. In addition, some FTMs decide

to transition without the use of testosterone.

3. Holly Devor,

FTM: Female-to-Male Transsexuals in Society, Indiana

University Press, 1997, p. 363.