Marcelle Cook-Daniels

Marcelle Cook-Daniels(March 1, 1960 - April 21, 2000)

FemmeNoir

A Web Portal For Lesbians Of Color

Marcelle Cook-Daniels

Marcelle Cook-DanielsMarcelle Y. Cook-Daniels, 40, died April 21 as

a result of suicide, following a lifelong battle with clinical

depression, according to his partner of 17 years, Loree

Cook-Daniels. A native of

Washington, D.C., where he lived until his 1996 move to Vallejo,

California, Marcelle was a computer programmer/analyst who

worked for the IRS, the Maryland-National Capitol Park and

Planning Commission, and, most recently, Norcal Mutual Insurance

Company of San Francisco. At the time of his death, he was

actively working toward his M.S. degree in Computer Science at

Golden Gate University.

A

quiet but very dedicated and principled activist, he was known

for his work in raising awareness of transgender and Lesbian/Gay

issues and for his efforts to promote and support his family

values of love, commitment, honesty, openness, and public

service. His education and advocacy work included presentations

at the 1999 Creating Change conference, the 1998 "Butch-FTM:

Building Coalitions Through Dialogue" event, several True Spirit

Conferences, and numerous other educational and advocacy events.

Interviews and/or photographs of him appear in the "Love Makes A

Family" book and tour; Dawn Atkin's book "Looking Queer: Body

Image and Identity in Lesbian, Bisexual, Gay and Transgender

Communities," and "In The Family" magazine. He was an active

supporter of COLAGE (Children of Lesbians and Gays Everywhere)

and provided substantial material and volunteer support to the

Transgender Aging Network, four True Spirit conferences, and The

American Boyz.

A

quiet but very dedicated and principled activist, he was known

for his work in raising awareness of transgender and Lesbian/Gay

issues and for his efforts to promote and support his family

values of love, commitment, honesty, openness, and public

service. His education and advocacy work included presentations

at the 1999 Creating Change conference, the 1998 "Butch-FTM:

Building Coalitions Through Dialogue" event, several True Spirit

Conferences, and numerous other educational and advocacy events.

Interviews and/or photographs of him appear in the "Love Makes A

Family" book and tour; Dawn Atkin's book "Looking Queer: Body

Image and Identity in Lesbian, Bisexual, Gay and Transgender

Communities," and "In The Family" magazine. He was an active

supporter of COLAGE (Children of Lesbians and Gays Everywhere)

and provided substantial material and volunteer support to the

Transgender Aging Network, four True Spirit conferences, and The

American Boyz.

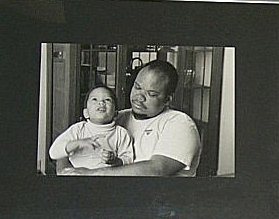

Marcelle

was at heart a family man. He was a devoted son to his mother

Marcella Daniels; a passionate supporter of his lifepartner of

17 years, Loree Cook-Daniels; and an outstanding father to his

6-year-old son Kai Cook-Daniels, who calls him, "The Best

Lego-Maker in the World." He is also survived by many beloved

friends and colleagues.

Marcelle

was at heart a family man. He was a devoted son to his mother

Marcella Daniels; a passionate supporter of his lifepartner of

17 years, Loree Cook-Daniels; and an outstanding father to his

6-year-old son Kai Cook-Daniels, who calls him, "The Best

Lego-Maker in the World." He is also survived by many beloved

friends and colleagues.

|

L: |

Let's start by you describing how you think of yourself at this point. |

|

M: |

I guess the phrase that I've come to is psychological hermaphrodite. It's the only thing that sounds like something that's both and neither at the same time. |

|

L: |

Well, if the hermaphrodite is psychological, then what is the physical? |

|

M: |

The physical is definitely more male. I think where the female comes in is emotionally, and in my approach to life and the world. My communication style is a little of each of what is traditionally thought of as male and female. And as far as relationships go, love is more important to me than sex. But, those things are just sort of broad-stroke stereotypes of male and female. |

|

L: |

I'm curious: when I asked you about the physical, you said that it was definitely more male. But if someone were to see you with your clothes off, they would have no question that your body is female. |

|

M: |

Now, you mean? |

|

L: |

Yes. So how do you resolve that? Or are you already living in the future? |

|

M: |

I guess I am already living in the future. I guess I've always lived in the future. I think that's part of the whole dysphoria. Let's use an analogy. Say you always think of yourself as being 5'10". And in your mind, or in your house which represents your mind, you have everything scaled so that in relation to it, you seem 5'10". And in your own little, safe corner, you are a 5'10" person. Your chairs and your furniture are all proportioned to make you look like you're 5'10". |

|

|

Then you go out in the world, and the world is scaled the way it usually is, and you realize that you're 4'10". To the world, anyway. But the way you've always thought of yourself, the way you've thought of yourself not in relation to other people, is as 5'10". So, I guess what I'm doing is something akin to having my legs surgically lengthened, so that when I go outside, people will see the person I always see inside. |

|

L: |

So you have been seeing yourself as male all along? |

|

M: |

Basically. It's kind of schizophrenic, I guess. My problem is mirrors and photographs and other people. I see myself a certain way, and then I'm faced with a "real" image that is very different from how I am in my mind. I feel I look a certain way in the world, am a certain way, and then something happens that changes that. Reality intrudes. |

|

L: |

Can you talk about a specific example of what might happen and how you might feel when that reality intrudes? |

|

M: |

Say I'm going out somewhere, and I'm picking out clothes and thinking of things that would work with each other. I'm thinking of a particular way I want to look, a particular image I want to convey. I take all this time and dress, and then when I check in the mirror to see how everything looks, there are these breasts that are staring back at me, and the shirt doesn't hang the way I thought it was going to. In my mind's eye, when I'm seeing myself, I don't see those. For instance, I like suspenders. But I'll put those on, and they bow out to the side because there are these huge impediments in the way. So I end up taking them off. |

|

L: |

That's an example of when you've met with your reality versus a different reality in the mirror. What happens with people? |

|

M: |

Well, there's the pronoun problem. I'm going out, and I think I'm really doing a good job of passing as a man and I'll get "ma'am"ed. Actually, sometimes it's nothing that obvious...it's just something like going into a building, and the guy in front of me stops to open the door for me. |

|

L: |

You're assuming he's doing that because you're female? |

|

M: |

Oh, yeah! It's not even an assumption sometimes. Sometimes I will stop and open a door, and try to wave the man on in front of me and he'll stop and say, "but that's not the way I was brought up!" |

|

L: |

Is it the breasts that make you female? |

|

M: |

I think that, given my other physical characteristics, it's the breasts that are the deciding factor when someone's waffling on the fence, trying to decide which way to take me. They are the most noticeable, prominent feature I have next to the freckles. Men can have freckles, but men usually don't have breasts, and if they do they're not 42 DDDs. I try to minimize that by the way I dress and the kind of clothes I wear, but I know that they're a focal point. I've talked to people before, men, and they're not making eye contact, they're looking at my chest. |

|

L: |

Aside from the breasts, you think you present to the world as fairly androgynous? |

|

M: |

I think I present to the world as fairly masculine. My body language, voice, facial expressions, I think all of those are sort of masculinizing cues. As Kate Bornstein said in Gender Outlaw, people are going to err on the side of male unless there's some feminizing cue, and so far the breasts have been the feminizing cue. I know, because I've been in situations where I've done things like wear pretty feminine earrings, but I've done things to conceal the chest, and I've still gotten "sir." So even dangly pearl-type earrings or something are not enough to convince someone that I'm anything other than a man wearing dangly pearl-type earrings. |

|

L: |

Which came first for you, looking kind of masculine or feeling masculine? |

|

M: |

Feeling. |

|

L: |

So the looking masculine you've cultivated. |

|

M: |

Looking masculine I think I've accentuated more, to counteract the physical presentation. It's also part of who I am. I was always a "tomboy." Even before I had breasts, I was always told I was acting more like a boy than a girl. I'm just much more aware of working at the appearance more, of having to think about it. So I don't know what I would be like if I didn't have to overcompensate for the physical stuff. I don't know if it would be much different or if it's just a part of who I am. The way I sit, the way I walk.... The testosterone helps too with the voice, the 5 o'clock shadow, the hair on my arms. I even have a receding hairline now. |

|

L: |

You started by describing yourself as a psychological hermaphrodite, but we've been talking "male" and "masculine." How do you reconcile those two? Or do you? |

|

M: |

When I'm talking "male," I think I'm talking about the physical presentation. I don't know about the rest of it; I haven't come to a decision about that. I just know that when I think of myself after the surgery, I think of myself as physically presenting as male, but what my identity will be and what I really will be...I don't know that it has any antecedent. |

|

L: |

So even though other people have changed their gender identities, you feel like you are forging new ground? A pioneer? |

|

M: |

Well, I'm not changing my gender identity; my gender identity has been fairly constant. What I'm changing is my gender presentation, I guess. I also don't think of myself as being a pioneer. I'm not a follower. I'm not a leader. I'm just doing what I have to do. |

|

L: |

In Stone Butch Blues, Leslie Feinberg talked a lot about the problems faced by people she defines as "he-shes." People who sort of confound other people's sense of the dichotomy between male gender and female gender. Would you say that the "he-she" analogy fits for you, first of all, and second, do you think you've had problems by not clearly fitting into "male" or "female"? |

|

M: |

Oh yeah. I've definitely had problems with fitting in. Take job interviews. I refuse to wear a dress to a job interview, because I'm not going to wear a dress on the job. I pretty much wear pantsuits. I have no doubt that I've gone in and people have thought, "oooh!" and not been able to deal with me on that level...I'm too butch. |

|

|

There have been problems with other professionals, doctors in particular. I've called my gynecologist's office and the staff has said, "I'm sorry, sir, this is a gynecologist's office," and I've said, "I know, I'm a patient, trust me." Or, dealing with salespeople. I'll walk up to the counter and they'll say "yes sir, er, ma'am." Then they're all flustered and they can't deal with me. I just want to say "pick one, it doesn't matter," and move on to the transaction. In Leslie's definition of a "he-she," I think that's the same thing I'm saying about the psychological hermaphrodite. I'm not all one or the other. I can't say how I'm going to feel two years down the road, but right now I think I "bend" gender and probably always will. At least, whatever percentage of my identity governs my physical self, that percentage is predominantly what would be considered "male". |

|

L: |

How early do you think you were perceived as a "he-she" or perceived by others as not fully fitting into the category of "female"? |

|

M: |

Probably from very early. As I said, I was a pretty severe tomboy, although I did like being around the girls better than I liked being around the boys. So it didn't necessarily follow a "straight" line -- identifying as male or female and wanting to associate with the same. I liked being a "boy" among the girls. I got a great deal of satisfaction about that, in more ways than one. I just pretty much thought the boys were awfully boorish. But I almost felt like an infiltrator with the girls. I felt like I was...that I was a pretender, that I was there in disguise. But I was still very tomboy-like, very physical, very daring. I did lots of climbing, rough- and-tumble type stuff. Also, I had a romantic interest in girls which is pretty common for a baby dyke. The girls were more willing to play "doctor" with one of their own than with the boys, so I got a lot of mileage out of that. The problem came in when I hit puberty. All of a sudden, inside of weeks, I started getting breasts, which were totally wrong, in my opinion. They got in the way. And they drew attention to me as a girl. People started saying, you're growing up, you've got to stop all these tomboyish activities. I was not about to stop. I didn't want to. Beyond that, I knew it just wasn't right. What was happening was just not me. |

|

L: |

The physical changes? |

|

M: |

Yeah. Up to that time, I was fine. Up until age 11, I had a flat chest, and I was fine. I had to deal with the period and what that meant, but by itself, that wasn't bad. That was hidden, so it wasn't a big deal. But the breasts were very noticeable, very out there. And very damaging to my self-image. |

|

L: |

If you could have had smaller breasts, would you have had an easier time, you think, staying in the female gender? Or settling into it? |

|

M: |

I don't know that that's true. I think if I had smaller breasts, I would've tried passing more often, earlier. I would've tried to pass altogether. I don't know that it would have made that much of a difference. I think I would have come to the same decision sooner or later. I think it would have just allowed me to pass more easily. |

|

L: |

Let's shift the conversation a little and talk about images of beauty. How does either the body you have that the world sees now, or the body you see in your head, relate to the images of beauty or attractiveness both in the society at large and in the Lesbian/Gay community? How does attractiveness figure into all this? |

|

M: |

I don't think of myself as an attractive woman. I just don't think I do "woman" well. I'm definitely far outside the mainstream beauty image. I've tended to play up the Lesbian butch image, but I don't know that I necessarily fit that either. When I think of Lesbian butch I think white. More specifically, I think somewhat tall or medium height, short hair, handsome features, Caucasian. I'm kind of pudgy, lumpy, big-breasted. I don't think I fit either straight or Lesbian. I think the straight ideal of female beauty is pretty narrow; very few women fit it. Admittedly, the body I see in my head leans more toward the masculine attractiveness ideal. I would like to be trim and fit and well-muscled, which to a degree I already have because I do have a muscular body that can be developed even more on testosterone. But again, even the gay male ideal or the straight ideal for men -- I don't think I fit that either. One, I'm too short. And two, I tend to think of that ideal as being white, also. |

|

L: |

So the fact that you're perceived as black almost by definition meant that you couldn't have been seen as attractive as either a male or a female? |

|

M: |

No. I wouldn't say not seen as attractive, but not the ideal, which as I said, fits very few people in this society. I have no doubt that some people may find me attractive, I think more so as male than female, but those would be people who don't necessarily accept society's view of ideal beauty. But even as a black, I don't have classic features. My complexion is too uneven. It would be better if I was all chocolate-brown, or all-tan, but not necessarily the mix that I have with the freckles. But other than that, I don't think I'm totally unattractive. I tend to think of my appeal as being somewhat idiosyncratic. |

|

L: |

So being black has affected your images of beauty. Has being black had any affect on how you see gender? |

|

M: |

Yes, I think it has. In the back of my mind I always knew that gender realignment would make me a black male in a society where black males are tolerated at best, and hated and feared at worst. That bias is something I have to get away from myself. I haven't had a real high opinion of most black men. I think of the exaggerated macho, fathering babies and abandoning them, that kind of thing. I think if anything, it's stood in my way of accepting my maleness. |

|

L: |

It would have been easier for you to have the feelings you have about your gender if you had been white... |

|

M: |

Oh, definitely! |

|

L: |

...because it would've been easier to imagine yourself as a white man than a black man. |

|

M: |

Most definitely. You and I have talked about television images and, in particular, [the TV show] Mod Squad before. I didn't identify with Link so much as I did with Pete. So I think it would have definitely been a lot easier to accept. But I gave up on being "white" when I was a kid. I didn't want it anymore. |

|

L: |

Given all that, when you're in that in- your-mind-"house" we talked about earlier, are you seeing yourself as a black male or a white male? |

|

M: |

Actually, I see male of indeterminate race. I see a mixture. Brown-skinned, decidedly, but mixed. |

|

L: |

But that's not necessarily how you define yourself out in the world, is it, brown- skinned and mixed? |

|

M: |

Well, I'm leaning more towards it. When I filled out a survey recently, they had a question about race. They had African- American, European-American, Asian- American, Native American, Other as choices. I put down "Other," and in the space for "Other," I wrote down African- American, European-American, and Native American. So, I don't know, maybe that's what I have to do now to accept the male: somehow downplay the "black" part. |

|

L: |

Because it's too scary to be a black man in this society? |

|

M: |

Maybe. Or maybe because I'm challenging what is male and female and whether one has to be one or the other, and that's making me wonder about all the categories. I don't know, really. My guess is it's probably a mixture. |

|

L: |

When we were talking about images of beauty, you talked about being pudgy. When we met, you were not pudgy. You'd lost a lot of weight and had worked out and were in very good physical shape. You were also taking testosterone and getting ready, to some degree or another, to go through with surgery. Over the years since, you began putting on weight and got out of shape. In retrospect, those were the years in which I blocked you from going forward with the surgery. Do you think there is a connection between your weight gain and being kind of "stuck" in being female? |

|

M: |

There is definitely a connection. That's funny, I was just thinking about that today. I was retracing the timeline. I think I stopped taking the hormones in '86, and I think it was right after that time that I started really porking out again. Looking back, I think I had an investment in my body before then. I started my weight loss program and everything when I was around 17, when I had decided that I was definitely going to go through surgery, this was what I wanted. I started to work out, and lose weight. Then when I was about 18 or 19, I started taking the hormones. At that point I also started to develop other physical characteristics I wanted: the growth of body hair, and then the voice deepened, and I became more muscular. My body was starting to be shaped more and more the way I wanted it to, and I started to take more care of it and appreciate it more and like it more. Then after we got together and it became clear to me that I wasn't going to be able to go through with it [surgery], I stopped taking the hormones because I just figured, "why? Why bother any more?" I started to lose that investment in my physical appearance again, and I just didn't care any more. I've noticed now that I've started to feel a little more like I care what I look like. Now I have a little more investment in my body. Unfortunately, it's a little harder now to get in shape than it was when I was 17! |

|

L: |

One reason it may be a little harder is because now you've had a baby. Can you talk about what it was like, as someone who's dealing with gender issues, to try to get pregnant, and then being pregnant? |

|

M: |

Originally, I had decided to be the one to carry the child because I thought that it would help me "be in my body," that it would help me "ground" myself in my female body. I thought the experience would make me accept the way I was more, so that I wouldn't have to keep dealing with the gender stuff. It didn't turn out that way. |

|

|

Getting pregnant was so goal-oriented, I don't know that I thought about it much. BEING pregnant was interesting. Being pregnant felt almost like there was some kind of parasitic creature in me. It didn't feel real, somehow. It just felt like some strange thing controlling my emotions and my body, and making me eat when it wanted to. If I didn't eat enough, it took all my energy and I didn't have any left. And just the movement inside, and all that.... It was very ungrounding as opposed to grounding. I dissociated a lot from my body. I wasn't able to deal with the experience in a positive way. I was sick all the time, and tired, and in pain. I definitely think part of that was the idea that I was a pregnant woman. And the more people paid attention to that, the more pissed-off I was. I didn't even want anybody at work to know until absolutely the last minute. |

|

L: |

Talk a little bit, if you can, about how it felt when people reacted to you as a pregnant woman, either people on the street or people you knew. |

|

M: |

Well, I don't think very many people on the street ever related to me a pregnant woman because I didn't do the "pregnant" stuff: I didn't dress pregnant, I didn't walk pregnant -- as far as I can tell -- I didn't act pregnant. At work, when it all came out, I had all these people walking around giving me unsolicited advice: [falsetto voice] "Oh, well, you've got to do this and you've got to do that and now you've got to breastfeed and this, that, and the other." All of a sudden everyone was in my business, and in my business about this in particular. People telling me what I should and shouldn't do: I shouldn't be lifting that, I shouldn't be doing this. And as a butch, the actuality was, I was functioning at a lower level and I couldn't do many things. I couldn't lift stuff, I couldn't reach for things, and I had no energy. So, my whole butch self- image which I'd cultivated all this time got really out of whack. The care people were giving me, making sure they carried things for me, opened doors for me -- it made me very angry. |

|

L: |

You breastfed the baby for awhile. Given how much upset your breasts have caused you all your life, was breastfeeding a problem? |

|

M: |

That's another way the dissociation came in. I didn't really think of them as my breasts so much as the source of his food. They ceased to become, in lots of ways, a part of my body. It was just sort of his meal, that's the way I looked at it. I wouldn't bear my breasts in public in order to breastfeed, but I get uncomfortable when other women do that, too. I really, at least I think I did, did a good job of separating myself from what was happening. |

|

L: |

The baby we were expecting based on sonograms was a girl. That's what we were prepared for. And then when you had the baby, it turned out to be a boy. Given your gender issues, what did it mean to you immediately and then later to have a boy? |

|

M: |

Well, the first time I heard he was a boy, I was coming out of the anesthesia [from a C-section] and I refused to believe them. I think I asked them about four times: "What did you say it was again?" "A boy." And I was like, "Oh, well how did that happen?" So there was shock. But I was also just plain relieved that it was over and he was here, and in some ways it didn't really matter that it was a boy. There was a little bit of disappointment. I was struck, actually, by what I took as sort of a metaphor for my life: We thought our child was a girl, and prepared for a girl, we had a girl's name picked out, and were all ready to receive this female, and it turned out to be a male! I thought about that as a metaphor for my life in that by all appearances -- my life being the erroneous sonogram -- I was a girl, but surprise!, I wasn't; I was a boy. Very early, within a few hours, I remember thinking, well, I wonder if his is a message. That this means I'm supposed to go through with it [gender realignment]. |

|

|

Later I started dealing with my disappointment in the fact that he wasn't a girl. I had to examine my feelings about males in general and my feelings about my being male, or my maleness.... I realized that I had to do some work to accept him being male, and that was the same work I needed to do to accept me. So in lots of ways, Kai's gender was another positive push. |

|

L: |

When you say you have "to do some work" to accept Kai's and your maleness, what do you mean? |

|

M: |

I had to start thinking, well, what is it...what are the problems I have with men in this society? And how much of those problems stem from the way males are socialized, and how much is irrevocably "male"? And so I had to sort of broaden and loosen my thinking about what males were and females were, and what they are capable of. I had to start looking at more of the paths or, sometimes, the lack of paths, that we're given to pursue based on perceived physical limitations, gender, height, or color, or any other sort of arbitrary means of measuring people. So I think it is in lots of ways making me less rigid about why people are the way they are, and how much of that is intractable -- how much of that is biological -- and how much of that is sociological -- how much we buy into the system. |

|

L: |

Given that, what do you think your transgender identity is going to mean for Kai? What are your hopes and fears about that? |

|

M: |

I don't really have a lot of fears. Hopes are that he won't be so rigid in his gender expectations. That he might be more capable of seeing people as people, and that he might be able to see degrees of maleness and femaleness and "otherness." And, hopefully, he'll be able to see that being a male or being a man has very little to do with just the physical, that it's a whole package that has to be developed. I mean, most people just kind of go through life saying, "I am what I am." They don't have to think about what they are, and what it means to be what they are. And I would hope that, given my experience, he would be more self-aware, and more self-examining about who he is and what he is, and why he is what he is. Just make him a much more conscious person in general. Not take things at face value. |

|

L: |

What are your hopes and fears about what will happen to you when your surgery is complete and your papers are changed and everyone has accepted you as male? |

|

M: |

Well, I do fear that I'll be perceived as "selling out." Regardless of what some people think, this is not about male privilege. That's something else that I had to fight in myself all along -- am I doing this just because men supposedly have it better in this society? That's another realization I had to come to. No, I don't necessarily think men have it better. So my fear is that people will assign the wrong motives to what I have done, and make certain assumptions about me based on those motives. That they may, for instance, think that I think being a woman in this society is so awful that I couldn't do it, that I had to cop-out. Although they do that now...make assumptions about me based on my perceived gender, or my sexual orientation, or my color. |

|

|

My hope is that I will be able to live openly as a transsexual or transgendered male, be up front about that and have people accept me for that, and not try to make assumptions about who I am. |

|

L: |

So what are your motives? |

|

M: |

My motives are just to have my...to have things in synch. I don't know how else to put that. I don't believe that when I have the chest surgery in late August, that there are going to be any really profound, immediate effects on my life. I mean, I'm not going to be suddenly richer, or handsome, or anything like that. I just feel I'll be more at peace with who I am, and more happy with the way I am. That's the whole point in going through all this. As for any long- term effects, changes...I'll just have to see as I go along. I can't really say what the future will hold. I just know it'll be better. |

Source:

http://hometown.aol.com/marcellecd/Erroneous_Sonogram.html

http://hometown.aol.com/marcellecd/Transgendered.html

Articles by Loree Cook-Daniels

Transgendered? by Loree Cook-Daniels

Transgendered can mean many things.

For a general discussion of some of the terms, read this article

from American Boyz's publication.

"Femmes, Butches and Lesbian-Feminists Discussing FTMs" by Loree Cook-Daniels — What are the ethics of non-trans people discussing trans identities? This essay poses a series of questions to help move the discussion in ethical directions.

"Birthing

New Life" — An essay by Loree Cook-Daniels on Marcelle's

pregnancy, the birth of our son, and Marcelle's decision to

transition. A version of this has been published in Mary

Boenke, ed., Trans Forming Families: Real Stories About

Transgendered Loved Ones (Walter Trook Publishing, 1999)

"Body

Parts" — An early essay by Loree in which she

understands that her fears about Marcelle's transition have more

to do with her than with Marcelle.

"Trying

to Keep the Boats Together" — A "Common

Ground" column on why we shouldn't be dividing the "T"

from the "LGB."

"Life

Stories" — What kind of paths do female partners of FTMs

take through transitions?

"TransPositioned"

— A nonfiction article on the issues facing lesbians when their

partners transition FTM.

Read the fantastic

keynote address Loree delivered at the 2000 True Spirit

Conference!

Growing Old Transgendered

by Loree Cook-Daniels

Are FTMs who have been on testosterone for 30 years more likely

to develop blood problems? Are there heart medications they

should steer clear of? Is 65 too late to have a phalloplasty?

Nine months later, a difficult rebirth has begun -- By

Loree Cook-Daniels

A Letter to Marcelle